By Jacob Palmer

WIU Student and Western Illinois Museum Intern

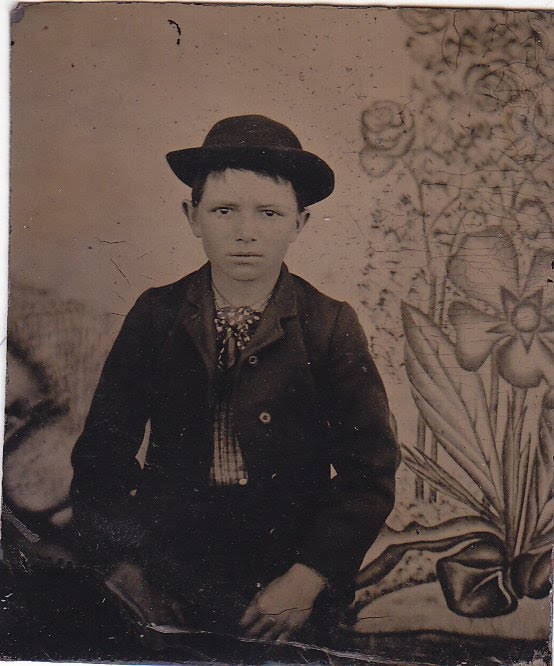

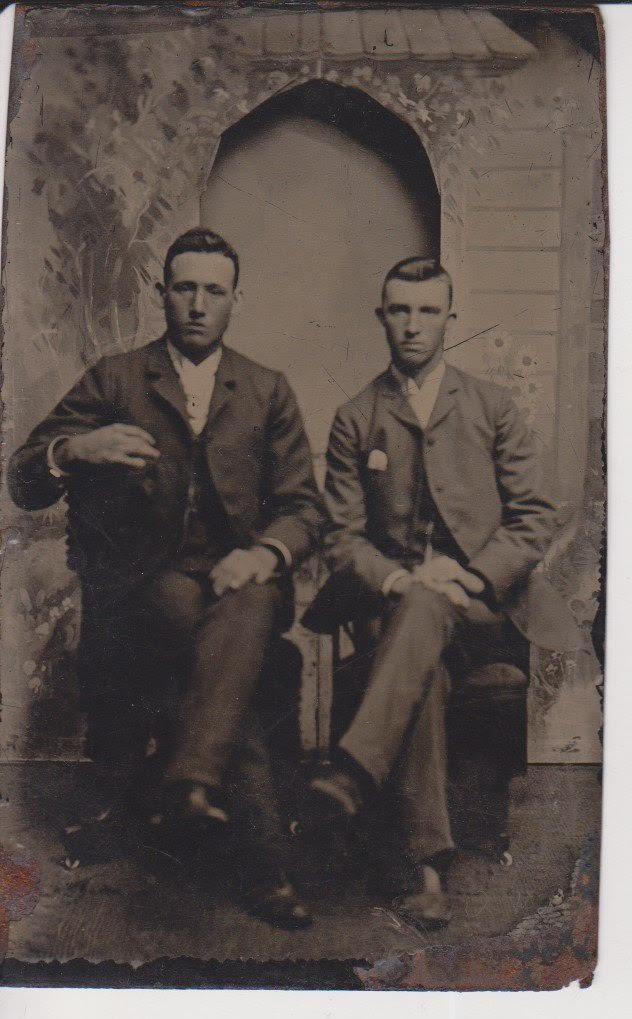

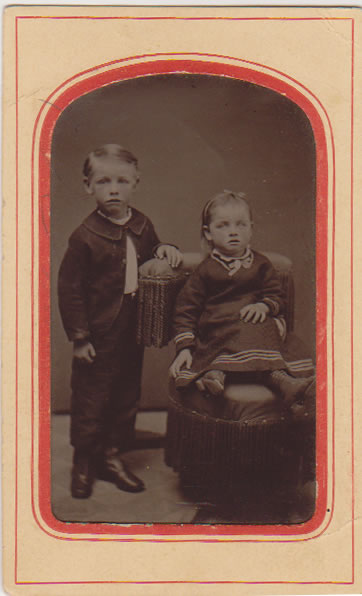

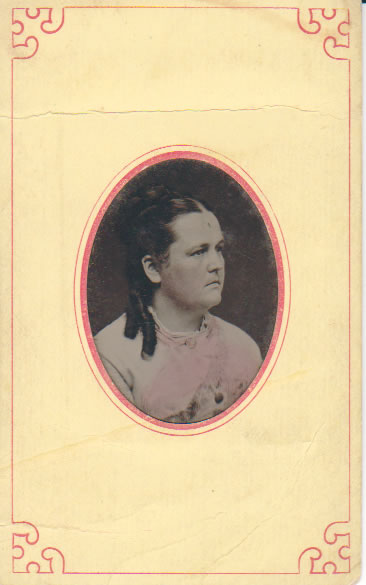

This month’s featured artifact is a selection of tintypes from the collection of the Western Illinois Museum. Tintypes, also known as ferrotypes, are photographs on thin sheets of metal, usually iron, which were used to document the images of individuals, families, and even places. They were used from the 1850s to the 1870s, being especially popular during the Civil War, due to the durability of the metal base. Tintypes were first created by a Frenchman, Adolphe-Alexandre Martin in 1853, and the tintype process was first patented in 1856 in the United States by Hamilton Smith.

Tintypes can be created by two different processes, a wet process, and a dry process. In using the wet process, photographers would spread a flammable, syrupy substance called collodion emulsion over a plate. While the plate was still wet and in the camera, silver halide, a compound with of silver and halogen crystals, was introduced onto the surface. Creating an image on the plate was dependent on the amount of time the chemical was exposed to light and the intensity of that light. Combining the collodion emulsion and silver halide caused a chemical reaction in which the crystals were reduced into tiny particles of metallic silver, which created the image. The dry process was similar to the wet process, but instead of using the collodion emulsion, it used a gelatin emulsion.

Tintypes came in a variety of sizes. The smallest, known as a sixteenth plate, measured 1.5 inches by 1.75 inches and the largest, the “mammoth plate,” was over 6.5 feet by 8.5 feet! The cost of an average tintype in 1861 ranged from 25 cents to $2.50. In 2020, these prices would equate to $7.00 to $73.00. During the Civil War, George S. Cook and other photographers would charge as much as $20.00 for a sixth plate tintype, which is 2.75 inches by 3.25 inches. Many people had a tintype made as a remembrance of their loved ones who had left home to fight in the war.

Interestingly, tintypes are not made of tin, they are actually thin sheets of iron. One way to tell the difference between tintypes and an earlier type of photograph known as the ambrotype, is if they are attracted to a magnet. The appearance of an ambrotype is similar to a tintype, but is made on a piece of glass with a metal backing. The metal used with an ambrotype does not have a magnetic attraction like a tintype made of iron. Tintypes, unlike a glass-plate ambrotype, were durable enough for soldiers to keep in their pockets while they were fighting.

The main reason tintypes were created was to help save time for photographers. Another type of early photograph which is slightly different from the tintype is the daguerreotype. Early methods, such as those used for the daguerreotype, took photographers a long time to process. With the processing time of tintypes being much shorter, photographers could take a picture and hand their customers the image in 10 to 15 minutes – not quite like a smartphone, but close!

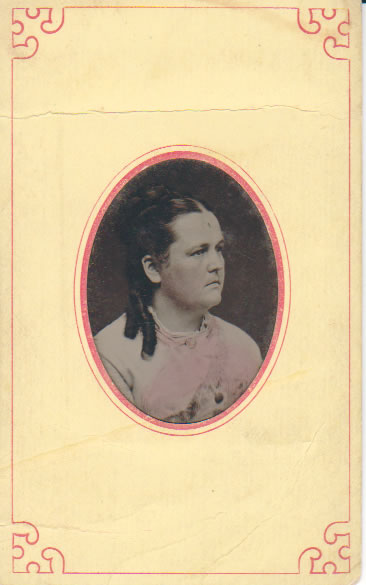

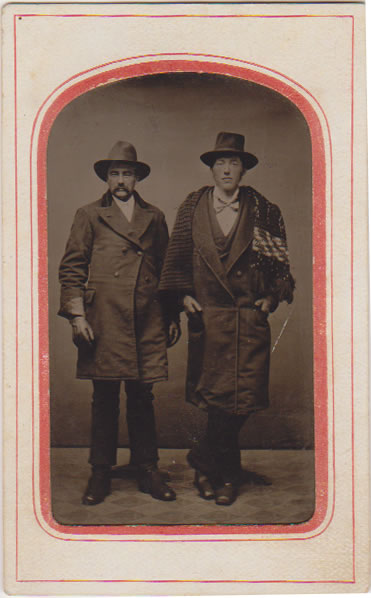

Decorative cases to display or keep tintypes in became popular in the 1860s. These cases hid the unfinished edge of the tintypes, as well as made them appear larger. Around 1863, tintypes were more commonly mounted in cartouche cards, a heavy cardboard card with a decorative oval-shaped window for the photograph. These cards were used until 1866, and by 1870, more elaborate embossed frames became common.

As tintypes became popular, they were widely available, including in Macomb, Illinois. There were several studios in Macomb, all located in the downtown square. One studio was owned by an Irishman named Thomas Philpot. He was born in 1833 and moved to Macomb in 1861. Located on the southeast corner of the square, Philpot, along with a man named Daniel Hawkins, started a gallery. In the gallery, the main photographs he and Hawkins produced were the ambrotype, carte de viste, and sometimes the tintype. In the 1870s, he moved his business from the southeast side of the square to the north side. That same year, he started to create albumen prints on cards, a process that involved adding an egg white onto a piece of paper and letting it dry. Once dried, the photographer would add a solution of silver nitrate and water to the card, which would cause the surface to be light-sensitive. Philpot produced an impressive number of photographs, and it was common for people to visit his store to view them. It is not clear why, but in 1885, Philpot decided to close his studio and work in a grocery store. Ironically, there are no photos of him that exist today. Philpot passed away in 1912 and is buried in Macomb’s Oakwood Cemetery.